Rethinking the Andromeda Paradox

What a Famous Paradox Can Teach Us About Time

1. Introduction

This essay, part of a Block Universe Series, looks at a well-known thought experiment in relativity - the Andromeda paradox. This popular version of the block universe argument was introduced by Roger Penrose and is sketched in this short BBC video. Here I show that the reasoning from this “paradox” to the block universe dissolves, once we look closely at what the physics actually says.

This essay is written for a general reader, but if you need or want any ideas clarified there are a number of explainer essays that go into more detail. This page gives links to these explainers, as well as the later essays which look at more elaborate versions of the block universe argument. There is also a short glossary at the end of this essay.

We’ll begin with a quick sketch of how relativity changes our picture of time, especially the relativity of simultaneity, which is central to the block universe idea, before outlining the Andromeda argument, and showing where it goes wrong.

2. From Universal Now to Relative Nows

Most of us have a simple idea of time:

-

The universe unfolds through time with a moment, ’now’, which is universal. The same everywhere and for everyone.

-

‘Behind’ now lies the past, which has already happened, and ahead of it lies the future, which has not yet happened.

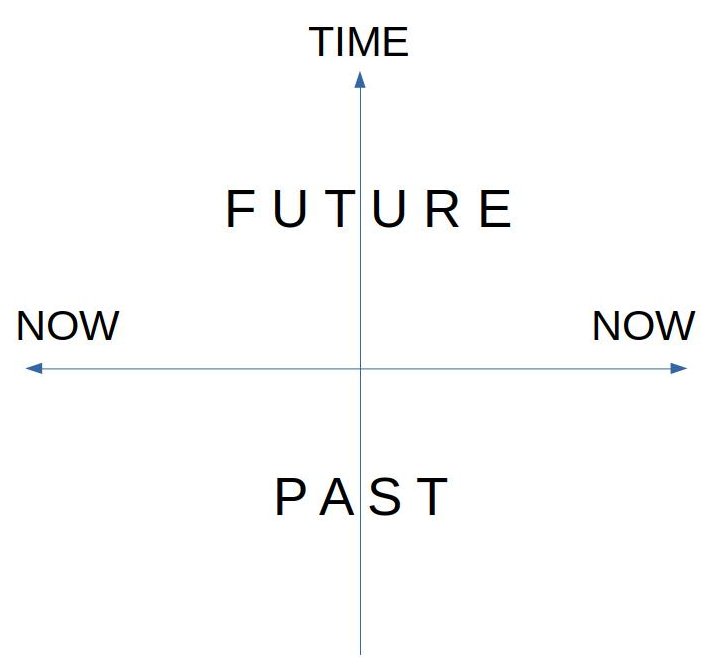

Diagram 1 captures this naive idea of time in picture form.

Diagram 1: Naive View of Space and Time

Each point on the Diagram marks an event - something happening at a place and an instant. The line going across the page represents all the events that are happening now.

This is in fact a naive version of what is known as a spacetime diagram in relativity theory. But the theory tells us three important things that force us to change this picture:

-

Light always travels at the same speed,

c, relative to all observers, no matter how those observers are moving relative to each other. -

Nothing can travel faster than light.

-

People moving relative to one another will disagree about which distant events are simultaneous with each other. There is no single, global ‘now’. This is what is meant by the relativity of simultaneity.

(If this strikes you as counter-intuitive, you’re not alone. The explainer essays unpack this and other ideas more fully, for those who want it.)

These facts combine to give us the following picture (I’ll explain why in a minute):

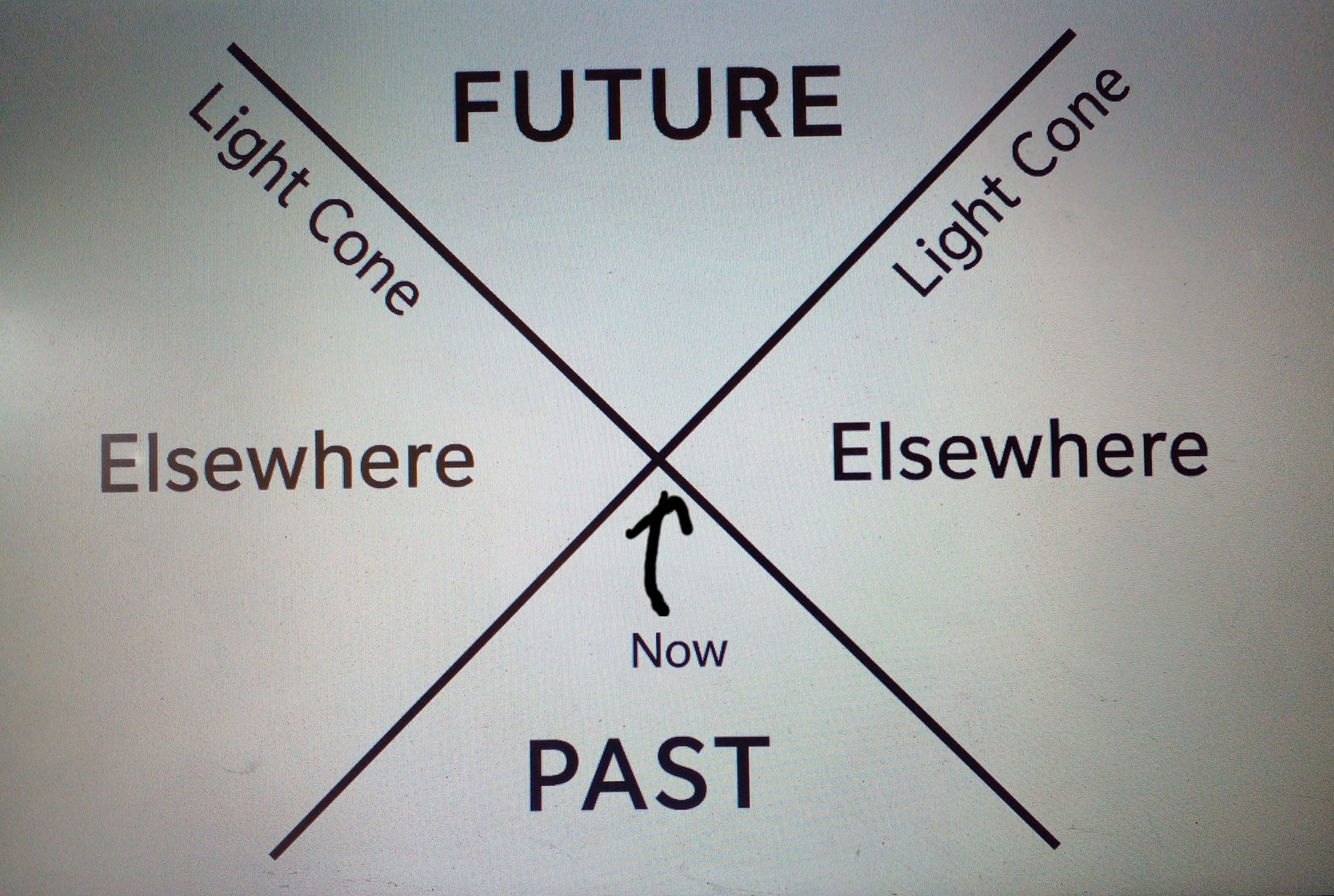

Diagram 2: Spacetime

Notice the following important differences from the naive, Diagram 1:

- The past is relegated to just the bottom quadrant, and the future to the top.

- Since there is no universal ’now’, the line in Diagram 1 is gone, and ’now’ is reduced to only the point at the centre - where we are here and now.

The other labels are best explained by showing a ‘3-D’ version of Diagram 2 - showing not just one, but two dimensions of space, or ‘distance.’

Diagram 3: A 3-D Spacetime Diagram.

The most striking features are the two light cones. The name light cone is used because the cones are the trajectories of rays of light. Everything outside of the light cones is simply called Elsewhere. The upper cone ‘contains’ the future and the lower cone contains the past. Diagram 2 is essentially a vertical cross-section of Diagram 3, so the cones appear as straight lines, and the ‘Elsewhere’ region appears in two parts on the left and right.

So why this picture? It comes down to the limit set by the speed of light. The only events that a person at the centre (x) can possibly reach, or which could be reached by a signal sent from x, are those which lie inside the future light cone. So these events comprise their possible future. Likewise, the past light cone contains all the events that a person at x could have come from.

Events outside those cones - in the so‑called ‘Elsewhere’ region - can have no causal connection to x because neither can affect the other without faster‑than‑light travel, which relativity tells us is impossible. So the geometry of the cones tells us important things about cause and effect.

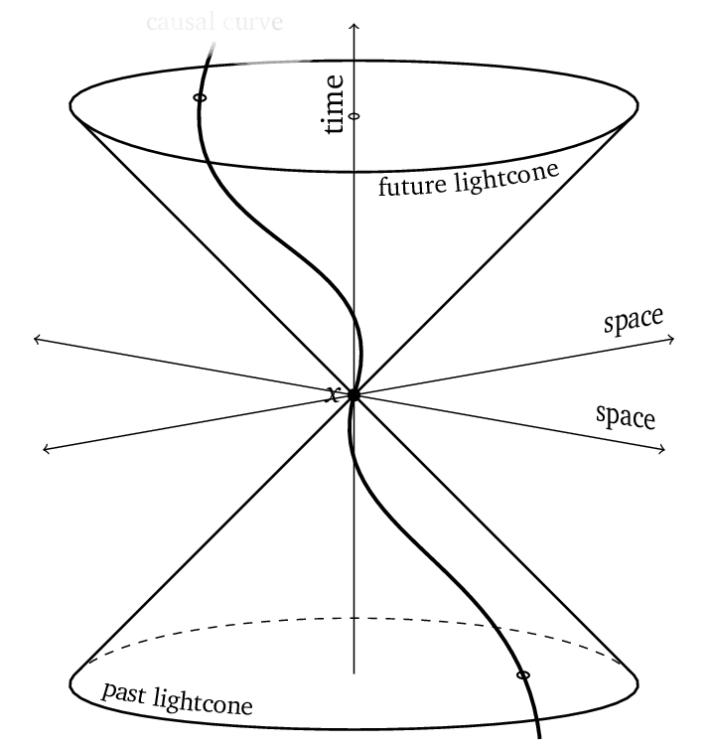

The relativity of simultaneity can be pictured as in Diagram 4, below.

Diagram 4: The Relativity of Simultaneity

A world-slice is a set of all the events that an observer judges to be happening at the same moment. It’s what each observer considers to be ’now’ - a ‘slice’ through spacetime of all the current events. It’s the same as the ‘NOW’ line in Diagram 1, except that instead of one slice which is the same for everyone, different observers will disagree where the slice is. The slices are ‘tilted’ relative to each other. They cut in different directions. This tilt between world-slices is exactly what relativity means when it says simultaneity is relative.

Diagram 4 shows what it means to say that simultaneity is relative: Mike and Melissa will disagree about which distant events are happening ‘now’. In particular, events in the distant Andromeda galaxy.

3. The Andromeda Paradox Explained

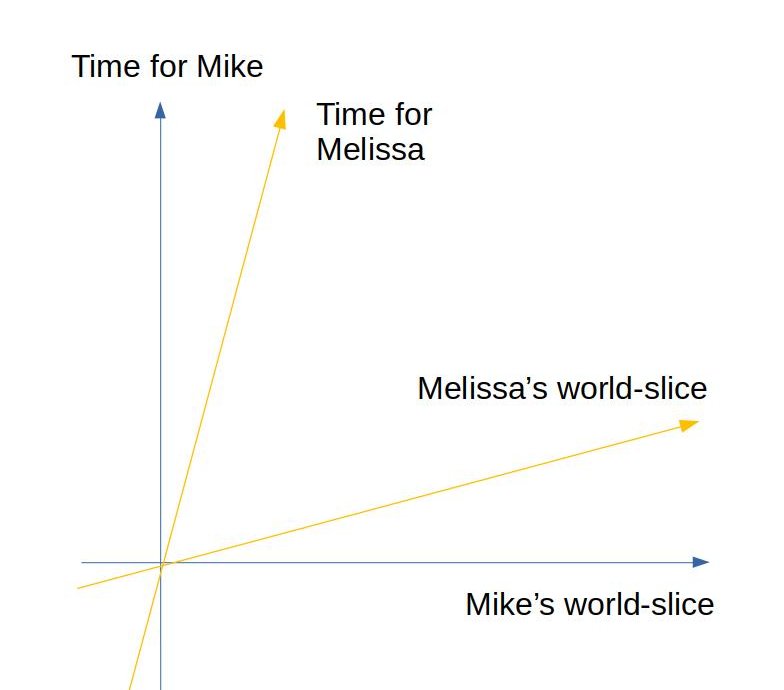

Roger Penrose’s Andromeda thought‑experiment makes these ideas dramatic. Picture two people, Mike and Melissa, passing each other in the street. They are in the same city spot but moving differently - say one walks north, the other south. Special relativity says they will disagree about which remote events are simultaneous with the instant they meet.

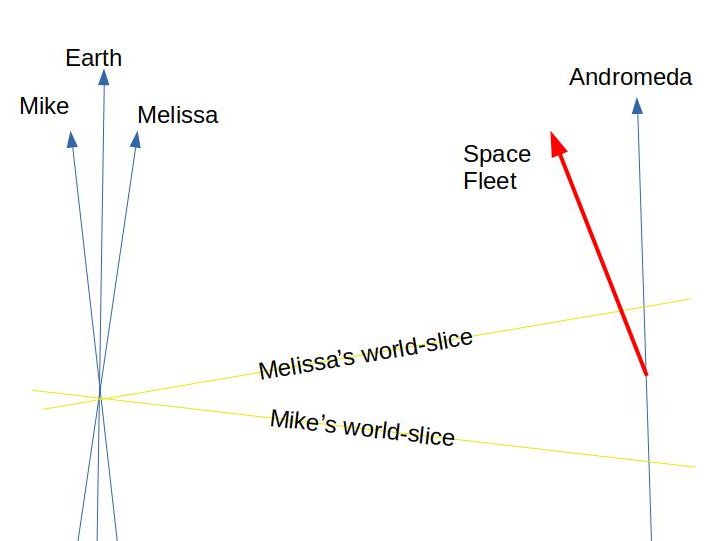

Penrose asks us to imagine an alien council in the Andromeda galaxy, deciding whether to launch an invasion fleet towards Earth. In one observer’s reference frame (Mike’s), the decisive vote happens tomorrow; in the other observer’s frame (Melissa’s), the vote happened yesterday. In this telling, at the moment they pass each other Mike would call the fleet’s launch a future possibility, while Melissa would call it a past fact. Diagram 5, below gives a sketch of how this comes about, given Mike’s and Melissa’s different world-slices.

Diagram 5: Invasion from Andromeda!

The intuitive leap: We all know the past is fixed, and since Melissa’s ‘past’ contains what is, for Mike, a ‘future’ event, then Mike’s future is already fixed. Extend that reasoning everywhere and you end up with the block universe: all of spacetime is already fixed.

4. Two Kinds of Past and Future

The Andromeda argument hinges on confusing two different notions of ‘past’ and ‘future’. The distinction between them is crucial, so I’ll introduce two terms to keep them apart - slightly odd-sounding, perhaps, but handy once named: timelike and framelike.

Timelike past/future: Refers to events inside an observer’s past or future light cones. These are the events that, in principle, can affect you (past cone) or be affected by you (future cone). So they relate to cause and effect. Only the timelike past and future correspond fully to our ordinary sense of those two words.

Framelike past/future: Refers to events outside the light cones. An event is in a person’s framelike future if it lies ahead of their current world-slice. Similarly for past. These labels depend on the reference frame a person uses.

(That may sound like an odd way to talk about time, but the explainer essays show how these two kinds of “past” and “future” arise directly from relativity.)

Relativity’s treatment of simultaneity applies only to events outside the light cones. All observers, in all reference frames, agree on which events lie inside the light cones, and which lie outside. So although observers may disagree about whether events outside belong in the framelike past or framelike future, all agree on which lie in the timelike past (or future) and which don’t. The relativity of simultaneity does not change the structure of cause and effect set by the position of the light cones; that part is absolute. (Despite what the name suggests, not everything in relativity theory is relative.)

This is why the light-cone picture matters: it separates the physics of influence (what can affect what) from the coordinate conventions that determine which events count as ‘now’ in a chosen frame.

Having made that distinction, we are ready to address the Andromeda argument itself. The flaw, once seen, is remarkably simple.

5. Where the Andromeda Argument Goes Astray

I’m going to lay the Andromeda argument out as a series of seven very short steps. This may look like overkill, but it’s deliberate. The flaw hides in what feels like a natural step of reasoning, and we’ll only catch it by slowing right down.

1. Mike and Melissa meet at the same place, but because they move differently they have different world-slices - True

2. The launch of the fleet lies on, or just before, Melissa’s current world-slice - True

3. The launch will not lie on Mike’s world-slice until tomorrow - True

Comment: There’s nothing at all wrong with these three statements. They are exactly what relativity tells us about how simultaneity depends on motion, as shown in Diagram 5.

4. In other words the launch, which is in the future for Mike, lies in the past for Melissa - True

Comment: True, provided we remember that we are talking about the framelike, not the timelike, past and future.

5. We can restate this: “Mike’s future is Melissa’s past.”

Comment: Here’s where the reasoning begins to slip. Not all of Mike’s future is the past for Melissa - not even all of his framelike future. And none of his timelike future lies in Melissa’s, or anyone else’s, past. We could say that some events in Mike’s future are already in Melissa’s past - but only in the framelike sense.

6. But since the past cannot be influenced, then the future cannot be influenced either.

Comment: We can accept a limited version of that: some future events can’t be influenced.

Which ones? Just those that lie “ahead” of Mike’s current world-slice but behind Melissa’s, and therefore outside Mike’s future light cone.

But we already knew that.

We explained it earlier, and without bringing Melissa into it at all. As we saw in section 4, no one can influence any event outside their light cone. This fact has nothing to do with predetermination - it simply reflects the finite speed of light, the ultimate limit on causal influence.

7. Since the future cannot be influenced, then it is already fixed.

Comment: This final step no longer follows. The immunity of some events to our influence doesn’t mean they already exist in the way the past does; it just means they’re too far away for any signal to reach them.

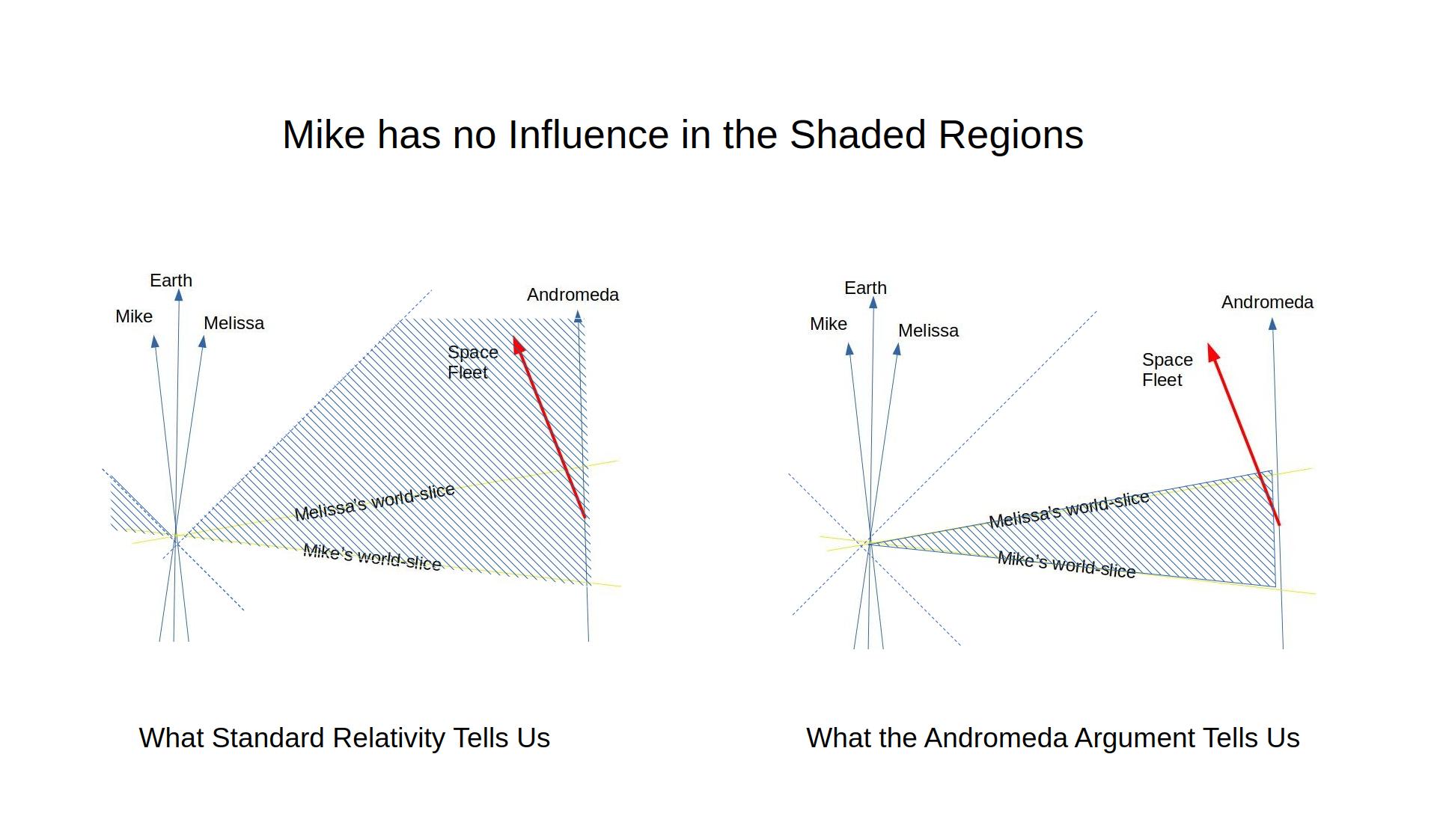

This side-by-side picture illustrates this starkly:

Diagram 6: The Andromeda Argument Tells us Nothing New

The whole “two-observers” set-up turns out to have been a red herring: it dresses up a simple geometric fact as if it were a deep truth about destiny.

It’s like missing the last post at Christmas. If, come December 20th, you realise your cards can’t possibly arrive on time, you don’t lament that you have no free will - you know it’s simply that you left it too late.

Relativity tells us the same sort of thing: it sets limits to what we can influence, but doesn’t tell us the future is carved in stone.

6. Where This Leaves Us

Relativity theory is about changing the coordinates we use to label events. It also imposes strict limits on cause and effect via the light cones. But it does not, by itself, show that the course of events is fixed in the philosophical sense of predetermination.

Have we demolished the block universe idea? Not quite. The Andromeda argument is a simplified version, and more sophisticated ones remain, which I’ll take up in Part 2. Yet however they’re framed, they rely on the same misconceptions.

The four-dimensional picture of the world belongs to physics. The block universe belongs to metaphysics.

Glossary

Most entries have links to in depth explanations in the companion essays.

Event. A point in spacetime (where and when something happens).

Reference frame. A choice of coordinates for referring to places, times, and events.

c. The velocity of light.

Relativity of Simultaneity. Which events are simultaneous is not an absolute fact, but depends upon the reference frame being used to describe them.

World‑slice. The set of events an observer calls ‘simultaneous’ with a chosen local event.

Light cone. The set of events reachable by light signals from a given event (future cone) or which could have sent light to it (past cone).

Elsewhere. The region of spacetime outside the light cones.

Timelike past/future. Events lying inside our past/future light cones, which we can influence or be influenced by.

Framelike past/future. Events lying outside our past/future light cones, with which we can have no causal connection.

Predetermination. The belief that the future is already fixed or “exists in advance.” Unlike determinism, it is a metaphysical claim about fate, not a physical claim about causation.

Spacetime Diagram. Essentially a distance/time graph like the ones we learn in school, but with time going up the page instead of to the right, and with features drawn from relativity theory.