Against the Block Universe Part I

Why the Argument for Predeterminism Falls Down

1. Introduction

Does special relativity imply that the future is already fixed and that free will is an illusion? A number of writers, including prominent physicists, have argued so. They often appeal to what is called the block universe: the idea that space and time together form a four‑dimensional ‘block’ in which past, present and future are all equally real. And consequently the future is already fully determined, and we can have no influence over it.

Minkowski’s insight that space and time can be treated together as one geometrical object underpins modern relativity. But the metaphysical leap from a mathematical picture of spacetime to the conclusion that the future is literally ‘already there’ goes further than the physics supports. The block universe argument depends on stretching key technical ideas — especially simultaneity — into philosophical claims the theory simply doesn’t imply.

This essay aims to show why. I target a popular version of the argument known as the Andromeda paradox, because it is vivid, simple and rests on the same confusions that underpin more technical forms. It is also fairly well known, and I can link to a BBC animation that sets it out! I will first sketch the relativity picture of time, then set out the paradox, and finally show where the reasoning slips. The physics is kept precise but informal enough for a careful non-specialist to follow.

2. Time in special relativity — the intuitive picture and what

changes

Most of us start with a simple idea of time:

-

The universe unfolds through time with a moment, ’now’ which is universal. The same everywhere and for everyone.

-

‘Behind’ now lies the past, which has already happened, and ahead of it lies the future, which has not yet happened.

-

Time always ‘flows’, from the past to the future, at the same rate everywhere, for everyone.

Special relativity challenges all of that.

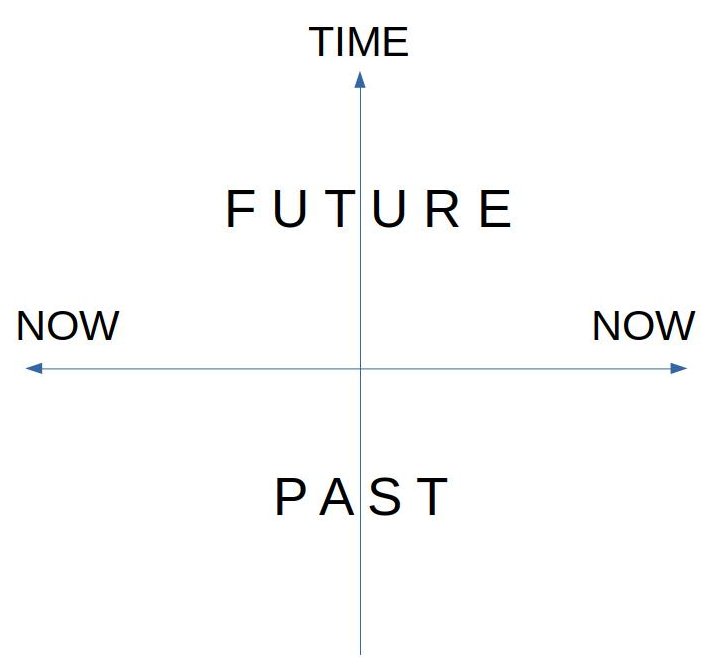

A handy way to get a feel for relativity is the space‑time diagram. This is basically what is taught in school science as a ‘distance/time graph’, except that here time goes up the page and distance to the right. Each point marks an event - something happening at a place and an instant. Diagram 1 captures our naive ideas of time:

Diagram 1: Naive View of Space and Time

The line going across the page represents all the events that are happening now. The line going up the page represents a person’s ‘journey’ from the past to the future. This path is called their world-line. This vertical world-line is that of someone who is stationary – they’re not moving either to the left or right. A tilted line shows someone moving.

Relativity tells us three things important for this discussion:

-

Observers moving relative to one another will disagree about what distant events are simultaneous with a given local event. There is no single, global ‘now’. This is the relativity of simultaneity.

-

Light always travels at the same speed,

c, relative to ’every observer. -

Nothing can travel faster than light.

These facts combine to give us the following picture:

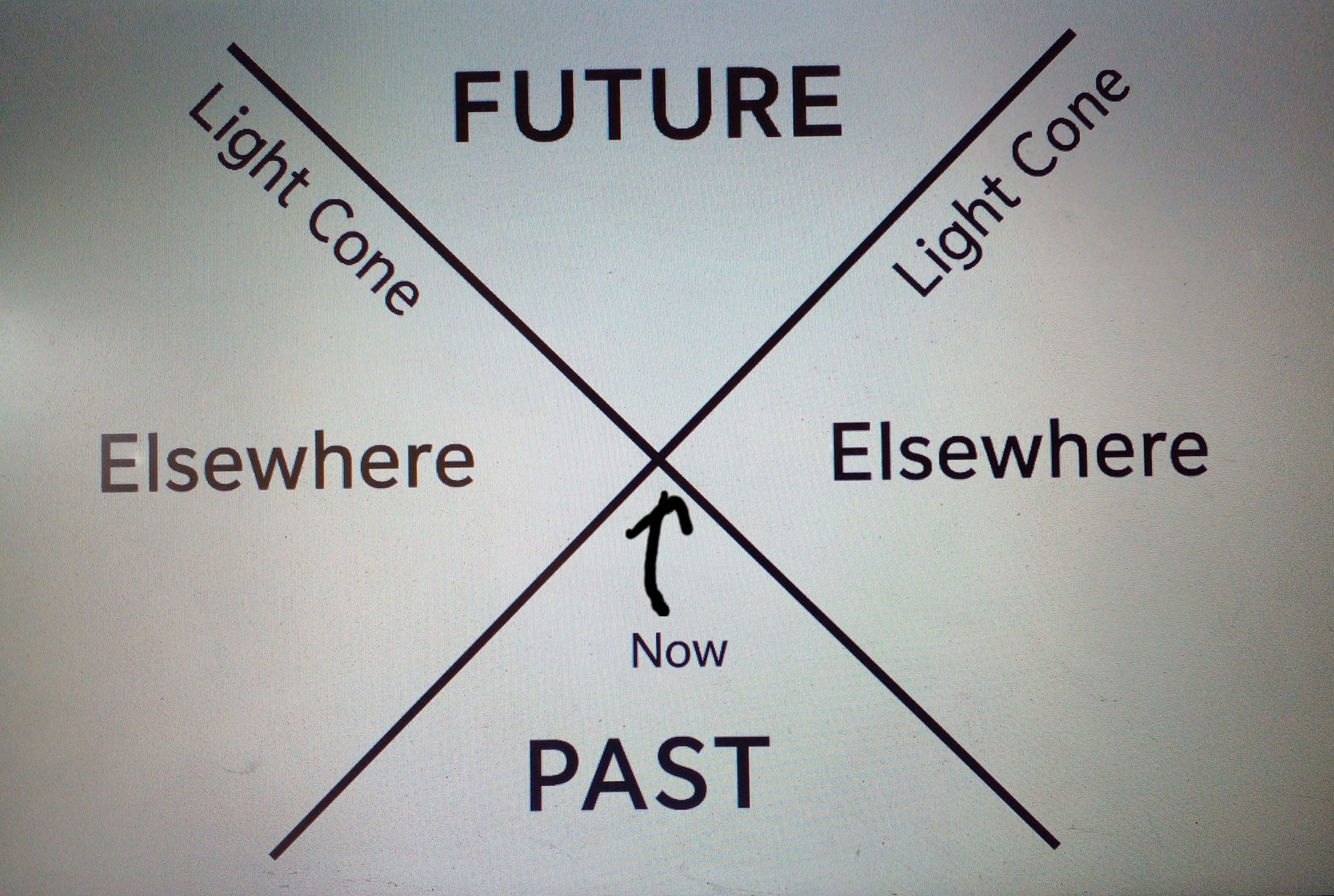

Diagram 2: Spacetime

Note the following important differences from the naive, Diagram 1:

- The past is relegated to only the bottom quadrant, and the future to the top

- Since there is no universal ’now’, the line in diag 1 is gone, and ’now’ is reduced to only the point at the centre - where we are here and now.

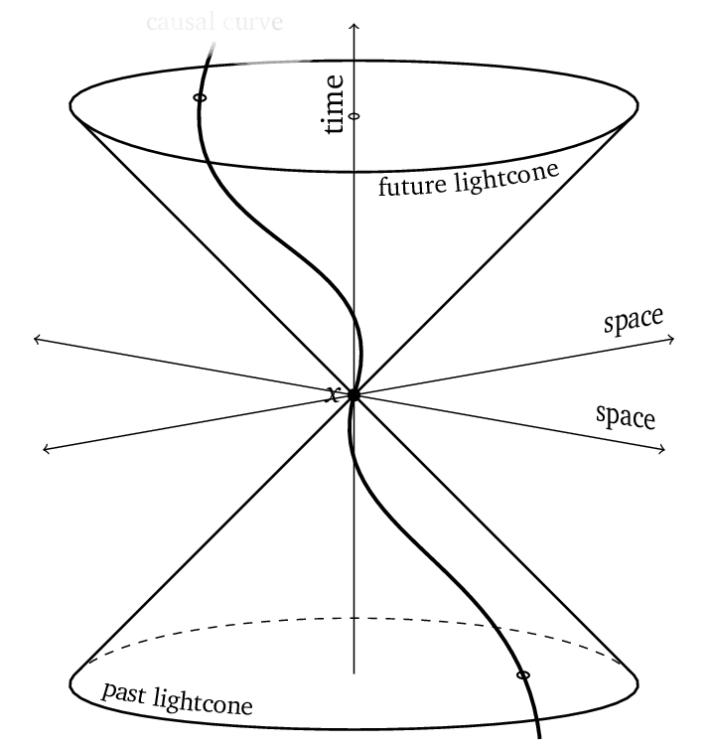

The other labels are best explained by showing a ‘3-D’ version of Diagram 2, showing two dimensions of space, or ‘distance’

Diagram 3: A 3-D Spacetime Diagram

The most striking feature are the two light cones. The name light cone is used because the cones are the trajectories (world-lines) of rays of light. Imagine an explosion occurring at x, in the centre of the diagram. The flash of light spreading out from the explosion will be an expanding sphere, but as only two space dimensions are shown what we get is an expanding circle, like ripples spreading out in a pond. When we add the time dimension up the page this expanding circle is represented by a cone.

Everything outside of the light cones is called simply called elsewhere. The upper cone ‘contains’ the future and the lower cone contains the past. Diagram 2 is essentially a cross-section of Diagram 3. In it the cones appear as straight lines, and the ‘Elsewhere’ region appears in two parts on the left and right.

So why this picture? It is due to the limiting nature of the speed of

light. The future light cone contains all the events that could possibly be

reached by a signal emitted at x, and the past light cone contains all the

events that could have sent signals to x. Events outside those cones — in

the so‑called elsewhere region — cannot be causally connected to x:

neither can affect the other without faster‑than‑light travel, which relativity

theory has shown to be impossible. So the points inside the future light cone

are all the events we might conceivably end up at in the future, and those in

the past light cone are the places and times we might conceivably have come

from.

A crucial Point: The relativity of simultaneity (RoS for short) concerns only events in the ’elsewhere’ region. Since the speed of light is the same for all observers the position of the light cones doesn’t change as you move between coordinate systems, and everyone agrees on which events lie inside the cones. RoS is a statement about coordinates — about how different reference frames ‘slice’ spacetime into ‘simultaneous’ sets. It does not change the causal structure set by the light cones.

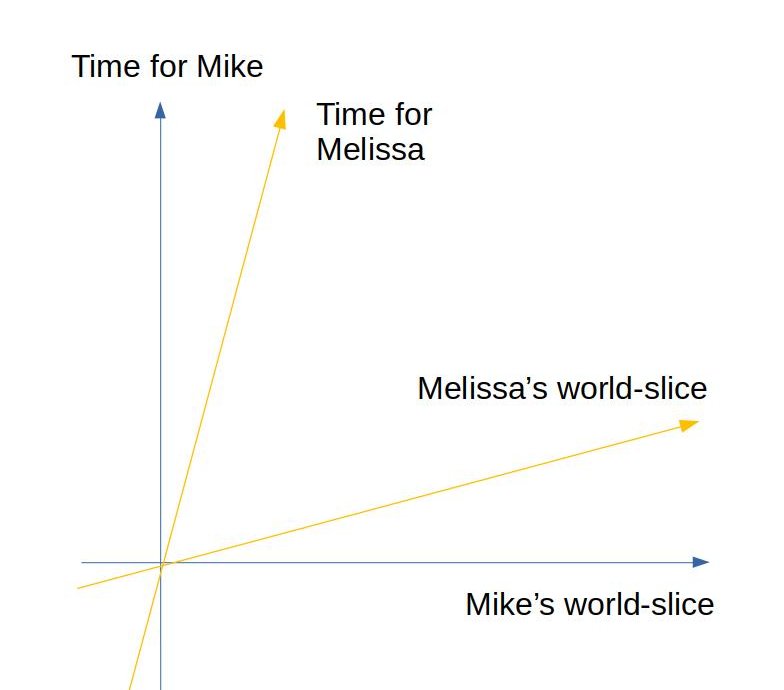

RoS can be illustrated in Diagram 4, below.

Diagram 4: The Relativity of Simultaneity

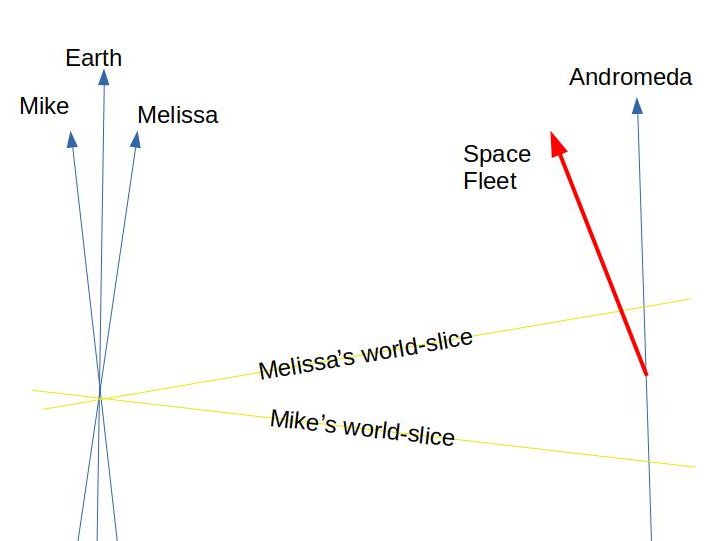

A world slice is a set of all the events that an observer judges to be happening at the same moment. It’s like a ‘slice’ through spacetime of all the current events. But each frame of reference has its own world slice. And the slices are ‘tilted’ relative to each other. That is, they cut in different directions.

What diagram 4 is telling us then is this: Mike and Melissa disagree about which events are happening ‘now’.

3. The Andromeda paradox, in plain terms

Roger Penrose’s Andromeda thought‑experiment makes these ideas dramatic. Picture two people, Mike and Melissa, briefly walking past one another on a street. They are in the same city spot but moving differently — say one walks east, the other west. Special relativity says they will disagree about which remote events are simultaneous with the instant they meet.

Penrose asks us to imagine an alien council in the Andromeda galaxy (about two million light‑years away) deciding whether to launch a fleet to Earth. In one observer’s frame (Mike’s), the decisive vote happens tomorrow; in the other observer’s frame (Melissa’s), the vote happened yesterday. So, the story goes, at the moment they pass each other Mike would call the fleet’s launch a future contingency while Melissa would call it a past fact. How this comes about is illustrated in diagram 5 below.

Diagram 5: Invasion from Andromeda!

The intuitive leap: since Melissa’s ‘past’ is fixed, and it contains what is for Mike a ‘future event’ then Mike’s future is already fixed. Extend that reasoning everywhere and you end up with the block universe: all of spacetime is fixed and unchanging.

In the rest of this essay I will refer to this lighthearted BBC animation, which spells out Penrose’s argument in more detail.

4. What relativity really tells us about past, future and causation

The Andromeda argument hangs on conflating two different notions of ‘past’ and ‘future’. The distinction between them is very important, so I introduce the following terms to distinguish them:

Causal past/future: Applies to events inside an observer’s past/future light cones. These are the events that in principle can affect you (past cone) or be affected by you (future cone). Knowledge and signals travel only along causal lines. Only the causal past/future corresponds to our traditional notions of past and future.

Coordinate past/future: Applies to events outside the light cones. These events may be labeled ‘before’ or ‘after’ a given event according to a person’s particular choice of time coordinate. We call the events they call ’now’ their world-slice. These labels depend on which coordinates you choose. Saying that such an event lies in my ‘future’ in this sense means that it is ’later’ than my current world-slice.

All observers agree on causal structure: whether one event lies inside another’s light cone does not depend on choice of reference frame. But different observers do not agree on simultaneity for events outside the light cones. That disagreement is a geometric fact about slicing spacetime, not a sign that causally significant facts are different.

To put it simply: if an event is in your causal future, everyone — in every reference frame — will agree that it is. But if an event is in the elsewhere region, some frames will assign it to your coordinate past and others to your coordinate future.

This is why the light‑cone picture matters: it separates the physics of influence (what can affect what) from the bookkeeping of coordinates (which events count as ‘now’ in a chosen frame).

We can only influence, or be influenced by, events in our future or past light cones. This is why I call them ‘causal’ past and future.

5. Where the Andromeda argument slips

Let’s restate the argument in simple steps, in order to pinpoint exactly where the mistakes lie:

-

Mike and Melissa are in the same location, but have different world-slices.

-

The launch of the fleet lies on, or just before, Melissa’s current world-slice.

-

That event will not lie on Mike’s world-slice until tomorrow.

-

In other words, what has just happened in Andromeda, as far as Melissa is concerned, will not happen till tomorrow, according to Mike.

-

So the future for Mike is already the past for Melissa.

-

Since it is a feature of the past that it cannot be influenced, then the future cannot be influenced either.

-

Since the future cannot be influenced, we have predetermination.

Let us examine these points in turn.

Points 1 to 3: All Correct

There is nothing at all wrong with statements 1 to 3. This is a consequence of RoS and is illustrated in Diagram 5.

Point 4: Acceptable With Care

Statement 4 is also acceptable, but we must remember that neither Mike nor Melissa has any knowledge of (and therefore no opinion about) what is happening in Andromeda. Their statements about simultaneity concern only the assignment of coordinates within their own reference frames.

So far, so good. But now the argument begins to falter.

Point 5: The Reasoning Slips

This is where we begin to go astray.

Firstly, not all of Mike’s future is the past for Melissa, not even all his coordinate future, and none of his causal future. We could, however, say that some events in Mike’s future are already in Melissa’s past. But only in the coordinate sense.

Point 6: Some Events Cannot Be Influenced

Given the previous paragraph, we can accept a modified version of statement 6: that some future events cannot be influenced. Which? Just those that lie ‘ahead’ of Mike’s current world slice, but outside his future light cone. In other words, those in his coordinate future.

But this is not controversial! We already knew this, and pointed this out at the end of the previous section. And without bringing Melissa into it at all. It has nothing to do with determinism, but everything to do with the finite velocity of light, and its role as the maximum possible speed for transmitting influence.

Point 7: Are Such Events Predetermined?

What now of statement 7? Are those events, which we cannot influence, predetermined?

No, they are not. Our powerlessness to influence some future events is not because of predestination. It is because no signal travelling at, or below, the speed of light can reach them, and the speed of light is the top speed. They are simply too far away.

Being unable to influence an event (because it is too far away) is not the same thing as that event being metaphysically fixed or predetermined.

Bringing in a second person’s reference frame was a red herring. It simply confused the issue, and disguised a sleight of hand. The supposed insight about determinism turns out to be a restatement of something we already knew: we cannot influence events outside our light cone. That has nothing to do with whether the universe is predetermined.

It’s akin to missing the last post at Christmas. If, come December 20th, you realise that your cards cannot now possibly be delivered before the big day, you don’t lament that you have no free will - you know it’s your own fault for leaving it too late.

6. Closing reflections

The past is fixed and cannot be changed (alas!). But it can have an influence on our current situation. The future is still mutable. We can influence it, but it can have no influence on the fleeting present moment, which lies between the two. Events inside the future and past light cones have these classical properties.

But we now realise there is a region of spacetime that is later than the past, earlier than the future, yet which we cannot call ’now’ either. ‘Elsewhen’ might be a more appropriate name for this ghostly region than ’elsewhere.’ And it has a curious mixture of the properties of past and future. It is like the ’true’ past, in that we cannot influence events in this region. But neither can those events have had any influence on our present. In that, it is like the ’true’ future.

Relativity reshapes our ideas of simultaneity and shows us that some intuitions about time do not survive scrutiny. But the correct lessons are subtle. Slicing Elsewhere, and calling events on one side the future, and events on the other side ’the past’ is a futile endeavour, since events on either side of the arbitrary demarcation line have precisely the same properties! In what sense is one a ‘future’ event and another ‘past’? Not in any meaningful sense.

And what about the ‘world-slice’ itself? Does calling one slice of events ‘simultaneous’ actually tell us anything about them? The true lesson to be learned is not that simultaneity is relative, but that it is meaningless. After all, simultaneity is not something anyone ever actually experiences directly. To do so one would have to be in two places at the same time. Simultaneity is something we deduce about events, not something we experience, and depending on our reference frame we can make different deductions. I would suggest that it is an outdated concept we would do better to abandon, or at least take with a pinch of salt.

Relativity theory is simply about changing the coordinates we use to label events. It also imposes a strict causal structure via the light cones. But it does not, by itself, show that the course of events is fixed in the philosophical sense of determinism.

The block universe picture is a tempting metaphysical gloss over the spacetime diagram: mathematics gives us a four‑dimensional geometrical object, and some take that to mean the future ‘exists’ just like the past. The physics, though, only gives us the geometry and the causal relations.

Glossary

Event. A point in spacetime (where and when something happens).

Reference frame. A choice of coordinates for referring to places, times, and events.

c. The velocity of light.

RoS. Relativity of Simultaneity.

World‑slice. The set of events an observer calls ‘simultaneous’ with a chosen local event.

Light cone. The set of events reachable by light signals from a given event (future cone) or which could have sent light to it (past cone).

Elsewhere. The region of spacetime outside the light cones.

Causal past/future. Events lying inside our past/future light cones, which we can influence or be influenced by.

Coordinate past/future. Events lying outside our past/future light cones, with which we can have no causal connection.